Civilians

This section looks at civilians’ experience of suffering and surviving in wars today.

The human experience of war has always been much wider than the experience of those who fight it in military forces. Most people experience war as poverty not violence.

War today is a social, economic and cultural disaster for hundreds of millions of people who never see or hear a battle.

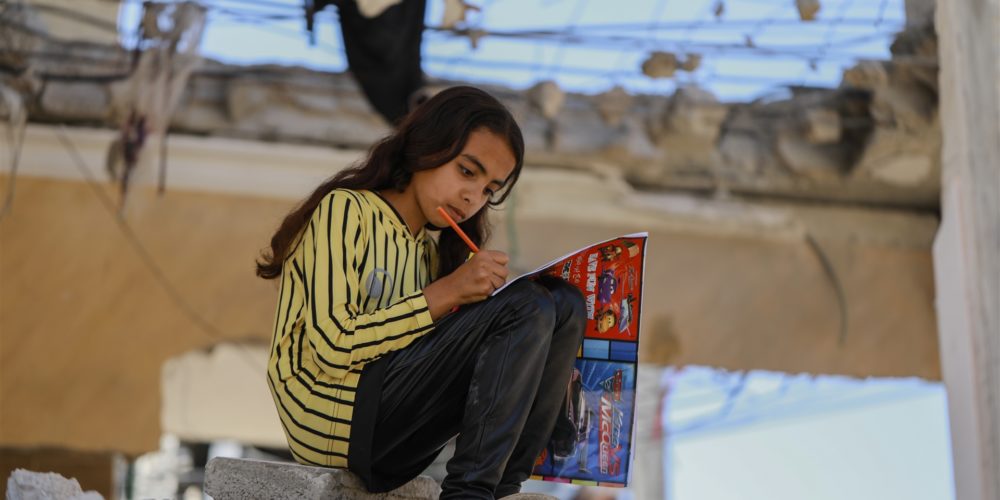

But people are also remarkable in war. They mostly do what human beings always do by surviving, acting and adapting, as people’s energy and agency are redirected to coping, caring and resisting the inhumanity of war.

We explore two sub-areas of civilians’ experience of war:

Civilian Suffering

Civilians as Survivors

Civilian Suffering

How much do we really know about civilian suffering in wars so far this century?

The answer is mixed because data difficulties still mean there is a lack of consistent information across the world, and humanitarian publicity sometimes misrepresents civilian suffering by focusing on particular groups and giving the impression that war is covering all areas of a country when it is not.

Civilian deaths

One thing we do know is that the number of civilians being violently killed in “battle deaths” is strikingly low compared to last century.

The same is true for civilian deaths from hunger, disease, impoverishment or inhuman treatment, which statisticians call “indirect deaths” from war.

This is good news.

The kind of militarily small wars being fought so far, and major new investments in humanitarian response are two reasons for this.

Violent “battle deaths”

Attempts to accurately count violent civilian deaths in war is a new and emerging science known as casualty counting, which is being pioneered by organizations like Every Casualty Counts and ACLED at and formalized in new standards.

Casualty counting is producing significant data on all forms of violent conflict. Brown University’s Cost of War project has been making a special study of combatant and civilian casualties in US wars since the early 2000s and has data for Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen.

The Brown University figures show two important trends. First, that in all wars except Iraq, combatant battle deaths are much higher than civilian battle deaths. Secondly, that civilian battle deaths in 21st century wars are low compared to 20th century casualties.

These are not narratives we usually hear from humanitarian agencies, human rights organizations or the media when discussing these wars. Instead, they tend to emphasise civilian battle deaths and give an impression of them as very high.

Indirect deaths

Famine and disease have historically been the major cause of indirect civilian deaths in war.

In the 20th century, devastating wartime famines and epidemics were tragically common. By contrast, in our century so far, there has only been one major wartime famine, i.e., Somalia in 2011. This terrible famine probably killed 244,000 people.

Reviewing data from several recent wars, Professor Paul Wise estimates that indirect deaths are typically double that of direct violent deaths because of the “destruction of essentials”, like livelihoods, healthcare, nutrition and shelter caused by war. This is also illustrated from a study led by Professor Francesco Checchi in South Sudan, one of this century’s worst long wars, which estimates that between December 2013 and April 2018 some 383,000 people died because of the war, including 190,000 people who were violently killed.

The Death-Displacement Ratio

War for most civilians today is experienced as a socio-economic disaster. The most fundamental feature of civilian experience in 21st century wars is displacement and impoverishment.

The fact that displacement rather than violent death is the main experience of most war-affected people today can be seen in the death-displacement ratio.

This compares the number of violent deaths in a conflict to the number of displacements caused by the conflict as people flee to avoid violent death or abandon areas made unliveable by danger and the “destruction of essentials”.

In the conflict between government forces and Boko Haram in northeast Nigeria, for example, this ratio stands at 1:160. In Yemen it is 1:333 and in Mozambique it is 1:265.1

1 In Yemen, ACLED report 12,000 violent civilian deaths by 2020 and UNHCR report 4 million IDPs. In Northeast Nigeria, the Nigerian Conflict Tracker reports 18,106 civilians killed in attacks between 2009-2021 at https://www.cfr.org/nigeria/nigeria-security-tracker/p29483 and UNHCR estimates 2.9m IDPs at 30 December 2020 at https://www.unhcr.org/uk/nigeria-emergency.html Mozambique’s figures are 3,100 civilians killed and 820,000 internally displaced, BBC, 6 August 2021, at https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/world-africa-58079510

Gender and Civilian Experience

Women and men, boys and girls experience the impact of war in different ways and in the same ways.

They are all vulnerable to bombing and raiding, to forced displacement, impoverishment, homelessness, hunger and disease. But they also endure different pain, violence, burdens and responsibilities in war because of the role their gender plays within the wartime society around them.

Typically, for example, women face greater risks of sexual violence, single parenting responsibilities, forced marriage and dying in childbirth from weakened health systems, while men face greater risks of forced military conscription, detention, summary execution, and migration.

A greater part of humanitarian and human rights attention in recent wars has focused on “women and girls” whose experience of war is estimated to be worse than men’s.

However, some feminist scholars of war, like Charli Carpenter are nuancing this greater concentration on the suffering of women and girls for two reasons:

- This view tends to overlook the experience of men, so making them the forgotten civilians who often remain invisible to humanitarian agencies and marginalized in aid programmes.

- A humanitarian and diplomatic concentration on female suffering plays into a damaging stereotype of women as weak victims when, in fact, they are often powerful agents of their own survival and key players in the recovery of their communities.

Civilians as Survivors

International humanitarian and human rights narratives, with their emphasis on victimhood and fundraising, still tend to lionize the agency of aid organizations and only partially allude to the agency of civilians themselves as the main actors in their own protection, survival and recovery.

In reality, aid agencies only ever help some of the people, some of the time in a few ways. Much of the ingenuity, energy, labour and social capital in people’s survival comes from civilians themselves.

Civilians take exceptional and everyday actions to survive in war.

Exceptional action includes life-changing action to flee, resist or build something new.

Everyday actions are less extreme but equally essential for survival. They include small but strategic actions that are endlessly repeated through a war, like: acts of kindness; avoiding threatening people and places; subverting unfair systems; pretending loyalty and respect; accommodating and negotiating with power, and queuing physically or digitally to be on aid distribution lists.

Civilian attitudes to war

Civilians do not simply suffer, survive and resist in war’s violence. Their wartime attitudes inform and shape the fight around them.

And civilians are not all ardent peace activists or politically neutral. Civilian populations typically present a range of different attitudes to the war around them and on what they consider fair use of force in the conduct of hostilities. Research by Professor Benjamin Valentino shows that the more civilians feel threatened, the more their views typically change to become more accepting of extreme levels of force against enemy forces and enemy civilians. Is not obvious that current attitudes towards military restraint will hold if the political and existential stakes rise around the world.

Civilian attitudes often make civilian populations important and influential audiences for politicians, armed forces and armed groups, whose communications specifically target civilian attitudes in various ways, either to win them over or to terrorize them in a constant struggle over civilian opinion and morale.

The Digital Civilian

Millions of civilians today live virtual lives alongside their physical lives. Their “digital bodies” are held as data in a wide range of government and humanitarian systems, and civilians organize much of their lives on mobile phones and online.

Digital 2021 reports that 66.6% of people in the world are unique mobile phone users and 59.5% are internet users, with 53.6% being active users of social media.

These rates vary widely in different wars. For example, in Yemen, 60.4% of people use a mobile phone but only 26.6% use the internet and 10.6% use social media. In Ethiopia, it is less, as 41% have mobile phones, 19% use the internet and only 5.5% use social media.

Digital connectivity and a virtual life can be a great advantage to civilians because it enables them to keep in touch with their family, their work and with government and humanitarian services. For example, many people now receive aid as cash transfers through their phones.

But connectivity can be dangerous too when civilians become the targets of misinformation, disinformation and hate speech, or their phone’s location is used to physically target them in some way. Data protection guidelines in humanitarian operations have become a priority. Failures in humanitarian data protection or the kind of criminal hacking experienced by the ICRC in early 2022 mean civilians lose their privacy and valuable personal data, which puts them in danger in various ways.

Explore the project

Dunant’s original humanitarian vision

Warfare today and tomorrow

Civilian experience of war