Warfare today and tomorrow

War now and next generation warfare

Solferino 21 examines the main dynamics of war between 2000 and 2021, and also looks at next generation warfare that is coming rapidly towards us.

Warfare so far in this century

Next generation warfare

Warfare so far in this century

In the first twenty years of this century, there have been wars in 54 countries of the world’s 193 countries, and most of these wars are continuing today.

Around 60 States and 100 armed groups were actively making war in 2020 according to the ICRC, with many other States supporting these wars in principle and practice as diplomatic, financial and arms-trading allies.

These early 21st first century wars have 10 striking characteristics:

Militarily Small Wars

Our century so far has not been an age of big wars. Early twenty first century warfare has caused terrible suffering but has been militarily small.

No massive armies, navies and air forces have clashed across, continents, oceans and skies as they did in the 20th century. The casualty rate, both combatant and civilian, has also been comparatively low.

Most wars between 2000 and 2020 involved an asymmetric struggle between relatively small government forces, armed groups and their Great Power supporters who have not fought each other directly but sometimes used State and non-state military partners in proxy wars.

Most battles have been relatively small too, with nothing on the scale of Solferino or large 20th century battles. The exceptions have been initial attacks in the invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, and some medium sized urban battles like Fallujah in Iraq, as well as Aleppo and Mosul in Syria. The Battle of Mosul lasted for seven months and involved an Iraqi force of 94,000 taking on an Islamic State Group (ISg) force of 12,000.

With the exceptions of Syria, Yemen, Iraq and sometimes Gaza, Afghanistan and South Sudan, most wars have also been confined to particular parts of a country and have not spread across whole countries (see ACLED, 2022).

Religious Wars with a Muslim Geography

Wars have mostly been fought within Muslim majority countries since 2003 (see Walter, 2017). This has often been because of the global meta-conflict between Islamist revolutionary movements – like Al Qaeda and ISg – and many States, but also because of conflicts against authoritarian Muslim governments as in Iraq, Syria and Sudan. Muslim populations have also resisted oppressive non-Muslim governments in Palestine, Myanmar and Thailand.

This largely Muslim geography is a change from 20th century wars where the two World Wars and many anti-colonial conflicts were centred in Christian, Fascist or Communist countries and spread across all cultural and religious zones of the world.

Internationalised Civil Wars or Armed Groups and Coalitions

Most warfare since 2010 has taken the form of internationalised civil wars with a large number of state and non-state armed groups and private military companies (PMC) fighting in coalitions on each side.

These alliances make early 21st century warfare an intensely crowded form of war with many different warring parties. This puts particular responsibility on State parties to ensure that the rules of war are being respected across their coalitions (see ICRC, 2021).

In 2020, the ICRC had contact with 465 armed groups around the world and large areas in contemporary warfare which are controlled by armed groups. This means that millions of people live “beyond the state” in wars today.

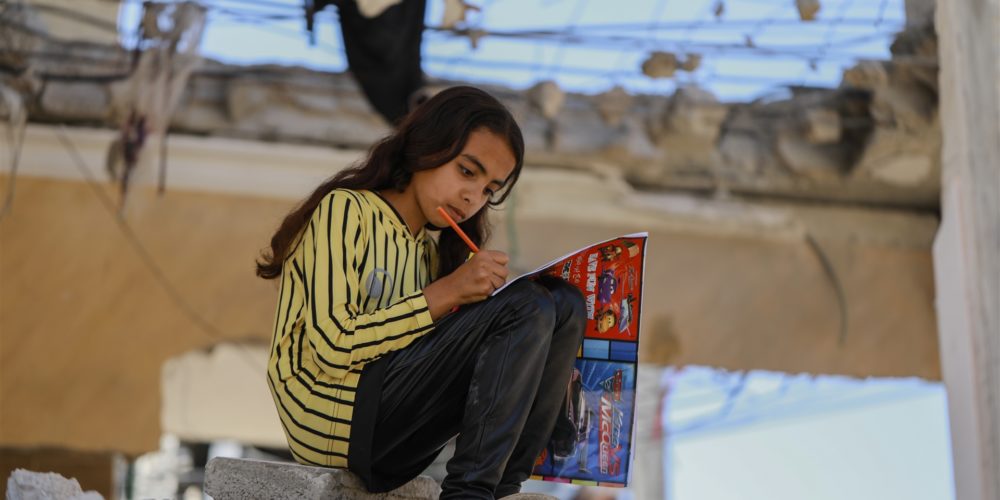

Urban Warfare

Increasing warfare in towns and cities is another trend in early twentieth century warfare compared to the more rurally focused insurgencies and counter-insurgencies that were more common in the later part of the twentieth century (see King, 2021).

The return of highly destructive forms of urban warfare is partly because urbanization is increasing so that strategic territory inevitably becomes more urban. But urban warfare is also rising because, in places like Afghanistan, Iraq, Syria and Yemen, several warring parties have been able to use significant airpower and artillery when attacking urban centres held by armed groups.

Alongside urban bombardment, the practice of siege and robust infantry campaigns within cities have also returned as major features of recent war.

The renewed prevalence and intensity of urban warfare has led the ICRC and the United Nations to call for the avoidance of explosive weapons with a wide area impact in urban warfare (see ICRC, 2022).

Long War

Long war, or protracted conflict as it is sometimes described, is a clear characteristic of warfare in the last twenty years.

Wars throughout history have often been long as well as short. Many wars are in fact new episodes of violence in long conflicts that flare up and down over hundreds of years, like the two world wars between Germany and its European neighbours or the series of wars in the wider Arab-Israeli conflict.

Wars today are also long because they mutate. A war, like Afghanistan, for example, started around tensions on the borders of the Soviet empire in the 1970s then led to invasions and occupation, mutated over time into national resistance, Soviet withdrawal, factional civil war, Islamist terrorism, US invasion, occupation and resistance.

Asymmetric wars, which are the majority today, are also notoriously difficult to win. When they involve so-called “radical disagreements” in ideology, they are equally difficult to end with a peace deal.

Chronic Political Violence

The most pervasive form of violence experienced by people around the world today is not all out war but an unsettled limbo between war and peace, or the intense violence of predatory gangs and organized crime.

This leads to the surprising conclusion that today’s wars are not the most dangerous places to be in the world currently. Extensive global research by Professor Keith Krause produced four striking findings:

“most lethal violence does not occur in war zones; the majority of states most affected by lethal violence are not at war; the level of violence in some non-conflict settings is higher than in war zones, and much of this violence is organized and in some sense political.” (see Krause, 2016).

Parts of Venezuela, Honduras and El Salvador are more dangerous places to live than Syria and Yemen in 2022. And yet, politicians and most international lawyers decide not to classify this very organized violence as war.

Looking ahead, unless there is a massive war between Great Powers, it seems clear that political violence is rising faster and spreading more pervasively than war, and may well be a bigger challenge to political order and human wellbeing. The traditional state-centric legal idea of war is looking a little old fashioned. It does not capture most of the organized violence that is killing, displacing and impoverishing people today.

Computerized Warfare

The changing technological character of war in the 21st century is the most original feature of war today because it brings real novelty to warfare. None of the other characteristics are unprecedented. Computerized technology, particularly Artificial Intelligence (AI), puts warfare on a new trajectory that challenges human autonomy and takes war and strategy into the new domains of outer space and cyberspace.

Most military fighting machines today are not complicated mechanical platforms like planes, tanks and artillery. Instead, they are highly complex “systems of systems” that are automated with extraordinary precision and speed well beyond the understanding of their individual human operator.

AI-based surveillance systems can gather extraordinary amounts of detailed information and function as “recommender systems” offering tactical advice to commanders in real-time. Drones are being used in attack, defence, surveillance and supply. They can operate alone or in swarms, and close-up alongside human combatants in “hybrid operations”.

AI-based weapons are achieving high levels of functional autonomy and may even be achieving “functional moral autonomy” as they make ethically-based decisions on their own.

Sub-threshold and Hybrid War

These two terms describe a mix of aggressive measures that fall just short of war. The covert use of Special Forces, espionage, assassinations, cybercrimes, disinformation campaigns and election tampering are often deniable and exist in a “grey zone”.

Sub-threshold and hybrid warfare is already the instrument of choice for Great Powers who seek to increase their sphere of influence without risking the huge costs of open war.

Western support to democratic movements undermining unfriendly authoritarian regimes, Russian subversion of Western elections and Chinese pressure to retake control of Hong Kong are all examples of sub-threshold strategy in action.

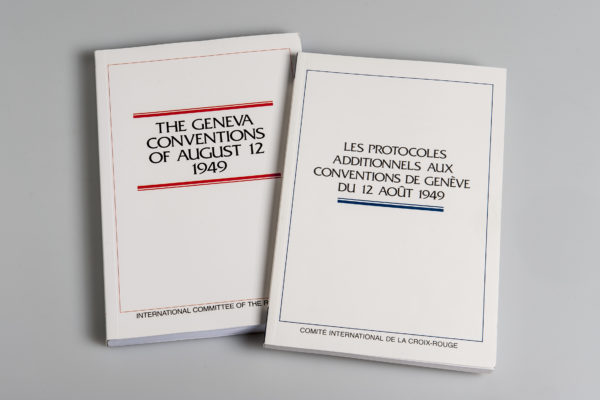

Hyperlegal Warfare

There are more laws of war today than ever before.

The First Geneva Convention in 1864, which was signed into international law as a result of Dunant’s advocacy, set in motion an almost constant process of law making and humanitarian advocacy for new laws that has continued through the 20th and 21st century.

Professor Craig Jones has rightly observed that the modern era is striking for a remarkable “juridifcation” of war in which battle spaces are “saturated” by international law about the lawful conduct of hostilities and the protection of civilians, the wounded and refugees. His work shows how hundreds of ‘war lawyers’ play an ambivalent role in limiting war today.

Some of this law involves simple requirements and prohibitions around actions that warring parties should always do or never do – like protecting the wounded or not deliberately targeting civilians. But much of the law relies on warring parties making judgements and interpretations of general principles like the “proportionality” of force and reasons of “military necessity”, which remain vague in law and highly contextual in conflict operations.

Despite the great elaboration of the laws of war, they remain problematic in practice for three reasons:

- The law is often complicated and dense, and only really understood by a professional class of highly specialized lawyers. Some of it can be boiled down into simple maxims but some of it cannot.

- There is a general weakness in the enforcement of the laws of war and usually no irresistible judicial or political incentive for warring parties to comply.

- The law can sometimes be bent to the advantage or disadvantage of one side in a strategy known as “lawfare” (see Martin, 2019).

These three flaws in the laws of war mean that people in war, or those watching war through the media, experience a sort of cognitive dissonance as they see endless wartime atrocities while simultaneously being told that there are laws for war.

Public Participation in War

War this century is communicated as never before. In Dunant’s day, picnic parties would watch battles from the surrounding hills. Today, billions of people are spectators of war or participants in war through their mobile phones and social media platforms.

Millions of people in war are using their social media accounts to visualize, record and describe the wars in which they find themselves as combatants, civilians, humanitarians, peacebuilders or activists for one side or the other. Millions of others watch wars from afar and join their information battles by taking sides as they like and share the messages they find.

The ancient art of propaganda, misinformation, disinformation and hate speech has also taken to social media at scale. Digital platforms are used to propagate a particular view of war by “weaponizing” accurate or false information and hoping it goes viral and “sticks” as the dominant narrative of a conflict. Individuals are also targeted directly through their phones – their geographical location discovered so they can be physically hurt, or their accounts bombarded with threats and stigmatization of various kinds.

Next Generation Warfare

Beyond the main characteristics of warfare in the last 20 years, we also look at the new kinds of warfare that are coming rapidly towards us, especially three main trends:

- Big war between Great Powers

- Ethical challenges with AI-based weapons

- War in a climate emergency

The Risk of Big War

As the world returns to a geopolitics of Great Power competition there is a risk of major peer-to-peer clashes between huge armed forces that would be very different to the asymmetrical and militarily small wars of the first 20 years of this century.

All Great Powers and regional powers today are preparing for largescale conflict that will see warfare across the traditional domains of land, sea and air but also rapidly expanding into three new domains:

Outer space

Military activity has now moved firmly into outer space which is already the military “back office” of terrestrial warfare. But space also looks set to be a site of conflict itself this century as achieving “planetary advantage” becomes the new challenge in war and the sure way to win (see Deudney, 2020).

Personal space

The personal space or domain is the third new domain. Here, warfare reaches deeply into the intimate human space of military personnel and civilians.

New developments in information technology and biotech will soon see significant bodily enhancements in individual combatants who will be increasingly fused with digital systems via gadgets that are attached to or implanted in their bodies. Augmented reality headsets and digital implants will see military bodies enhanced by technology to become multi-domain combatants. Biotech enhancements will deliver new drugs to increase stamina, reduce fear and heighten perception, as well as exoskeletons for greater speed.

Civilians who live increasingly virtual lives alongside their physical lives can also expect to find warfare played out through the phones, laptops and the wider “Internet of Things” as they may be targeted by surveillance, misinformation, disinformation or hate speech, and as their digital access to information, finance and public services becomes the object of attack and defence in cyber warfare.

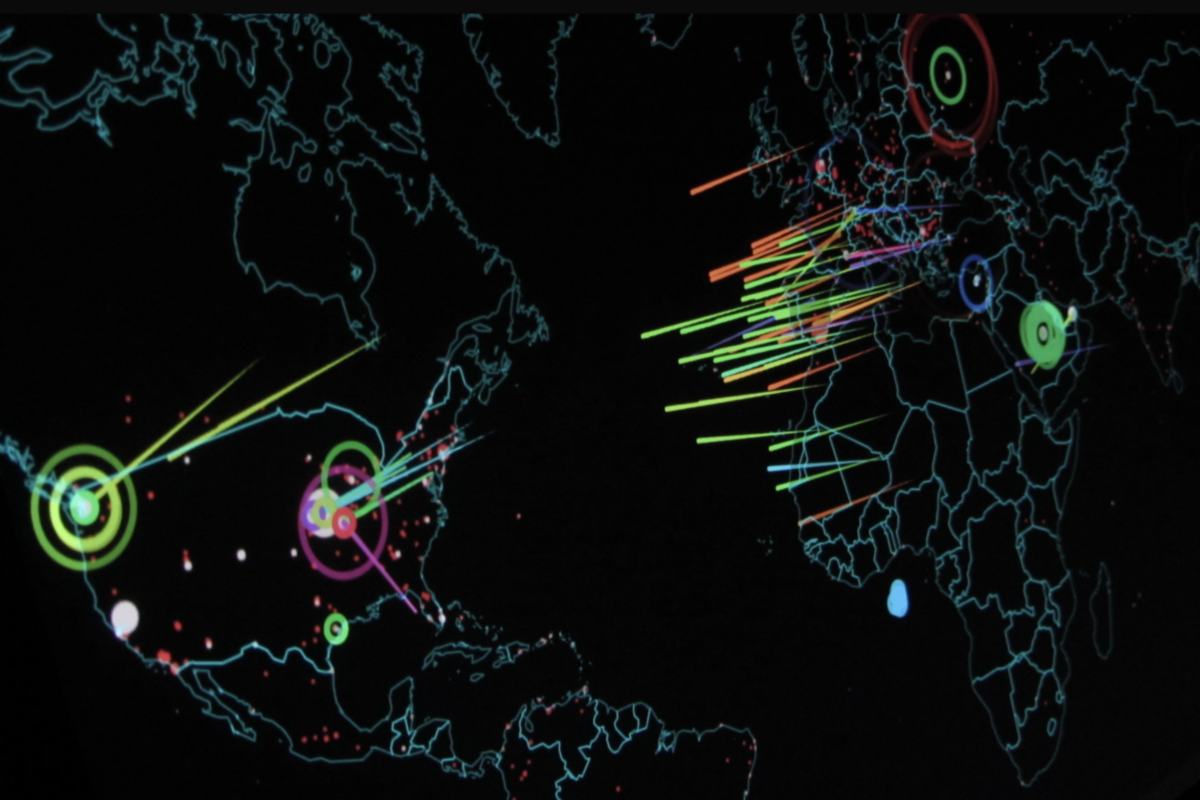

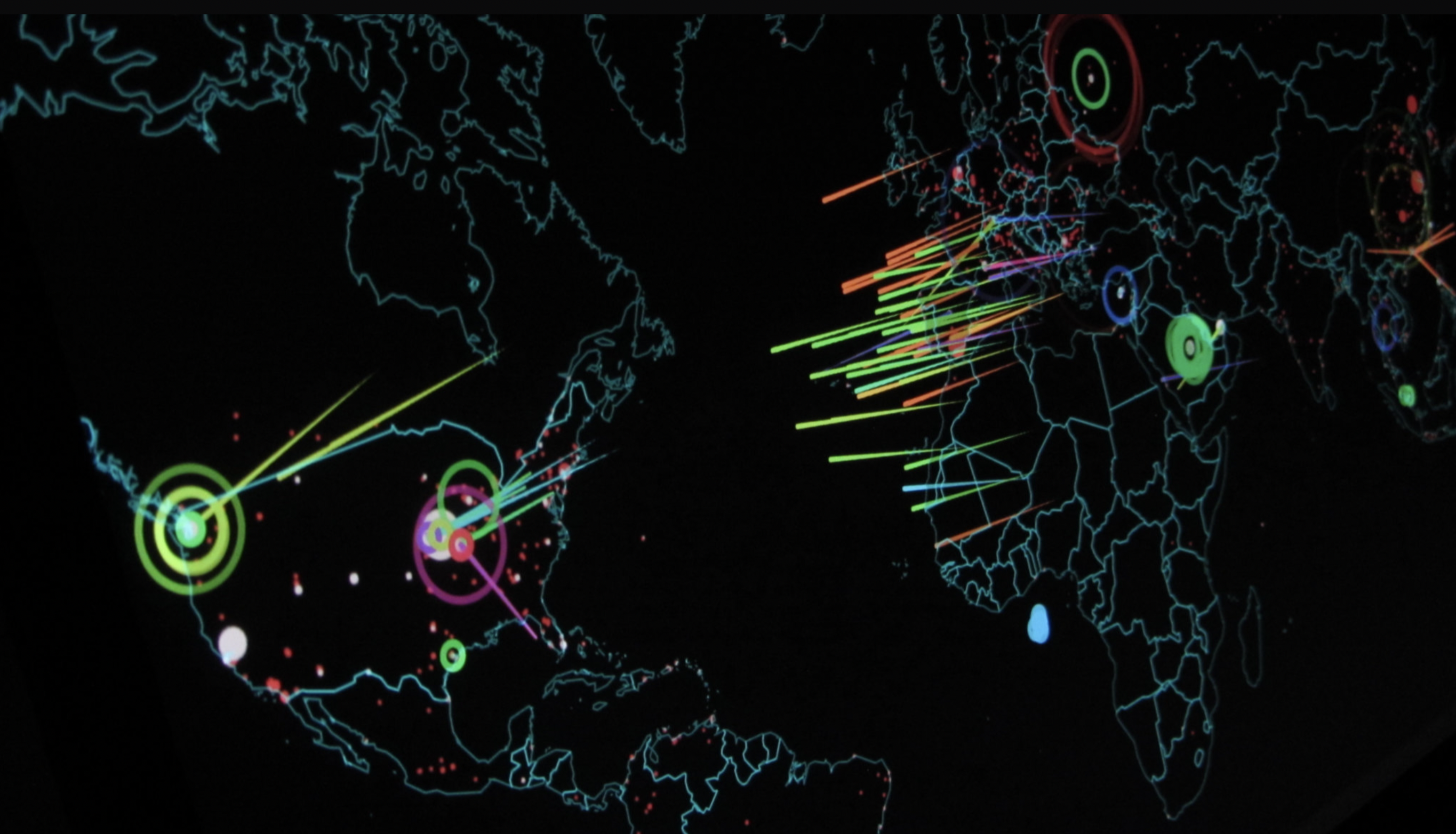

Cyberspace

Cyberspace is the second new domain of new generation warfare. This is distinct from “kinetic” AI-based systems of surveillance, supply or weapons platforms, which watch, support or attack people in physical space. Cyber warfare operates within the virtual space of computer programmes. Inside these programmes and systems ‘cyber combatants’ spy on the enemy or attack their systems while defending their own.

Even more than the aerial bomber of industrial warfare, cyber warfare has extended the operational surface of war today. A whole society is potentially open to attack in our interconnected world where so much of our infrastructure is dependent on information and communications technologies and so much of our personal life, our finance and our access to healthcare and public services is rooted in our personal computers and the “Internet of Things”.

The ethical challenge of AI-based weapons

A great part of the 21st century arms race is a dash to secure advantage in new digital and AI-based technologies. This is revolutionizing warfare and creating forms of violence and weapons that we have never seen before, except in sci-fi movies: invisible weaponized spaceships; autonomous fighting “warbots” with operating systems working at extraordinary speed, and cyberattacks that use keyboards to bring states and cities to a stop in major areas of modern life.

Increasingly autonomous lethal weapons rightly create anxiety because they produce significant ambiguity about whether they are still weapons under human control or non-human combatants making their own decisions in real time. In his book I, Warbot, Professor Kenneth Payne compares previous weapons with new AI-based and writes that: “they were tools, whereas AI is an agent.”

Ethical concern about AI-based warbots and algorithmic violence is focused around three areas:

Judgement

How can we be sure that warbots are ethically programmed to respect the laws of war?

Responsibility

Who is responsible for an autonomous weapon if it goes rogue? Is it the military, the manufacturer, the machine itself or some form of “hybrid liability” that begins to recognize non-human responsibility alongside human responsibility?

Human authenticity

Will the true significance of war and suffering diminish if humans are no longer doing the killing and hurting directly?

Warbot ethics are developing fast, but it is highly likely that ethics and law will have to play catch-up as new technology is designed and used before ethical codes and appropriate laws are agreed by States. The ICRC is working hard to encourage states to agree limits to AI-based weapons. But states decided not to pursue a new treaty on the matter in December 2021.

War in a climate emergency?

Climate crisis, as well as big war and new technology, is driving security thinking today. Alarmingly, climate extremes may be changing from being a condition of warfare to a cause of war.

In the next 10 years, climate crisis will transform military forces. Hundreds of military bases around the world are vulnerable to climate change and will need to relocate to avoid extreme flooding and heat.

Climate crisis will also create a new geography of economic value. Previously productive areas will heat up and dry out. Many littoral zones will become unliveable because of flood and storm. Oil and gas territories that were highly prized in the carbon economy will lose their economic and political value. Military withdrawal from these areas that were previously strategic for food, oil or trade will be followed by new military positioning around areas like the Arctic that have new strategic value as they warm to become newly productive. Armed forces will also have to adapt to volatile and extreme weather conditions while campaigning.

Many military forces are also beginning to take up the challenge of greening their installations and equipment to become net zero and to maximize renewable energy like solar and batteries that could dramatically reduce their operational costs and their logistics.

It is also increasingly likely that climate change will become a cause of war in the 21st century. Climate crisis is already changing the political and economic geography of what is valuable and what is not in regions around the world. Competition over this changing geography may well arise. So too may armed conflicts over adaptation and mitigation if one state’s adaptation is another state’s deprivation because of water-hoarding, deforestation or contested geoengineering.

Explore the project

Dunant’s original humanitarian vision

Warfare today and tomorrow

Civilian experience of war