Humanitarians

Humanitarian progress and the need for change

The 160 years since Dunant’s urgent call for humanitarian reform have seen extraordinary progress in the expansion and professionalism of humanitarian aid in war.

Here we look at the progress made so far and the need for further change as 21st century humanitarians face the possibility of big wars and climate crisis.

Humanitarian Progress

Changing Humanitarians

Humanitarian Progress

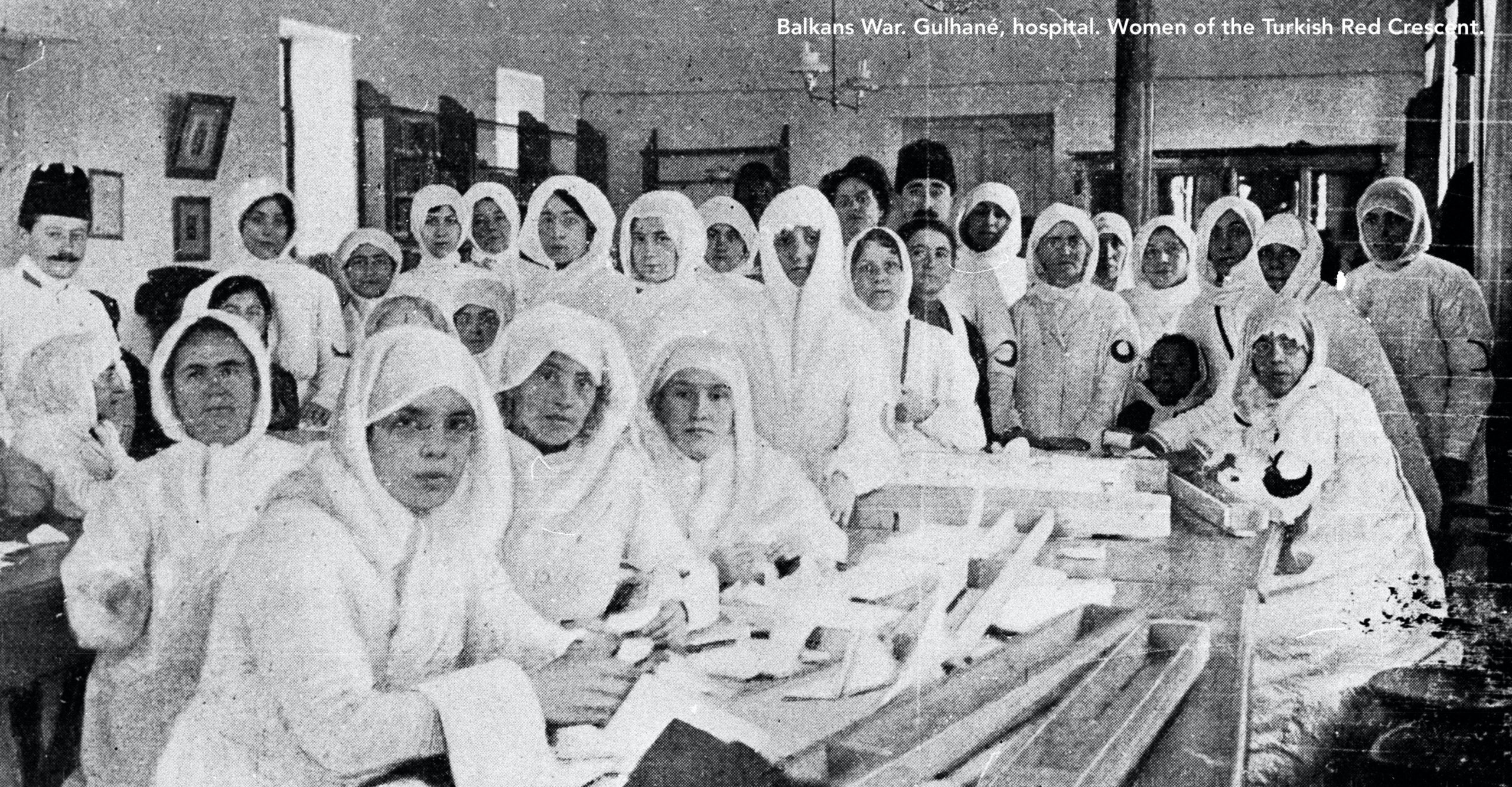

Soon after A Memory of Solferino’s publication in 1862, Dunant’s Red Cross Movement began to develop into a global humanitarian network, and in 1868 the Turkish Red Crescent became the first of many National Societies to bear the Red Crescent emblem.

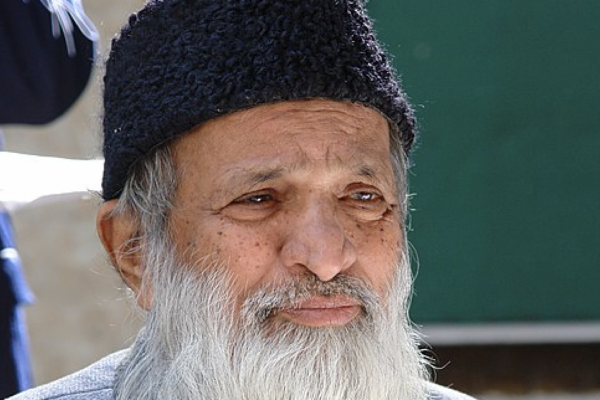

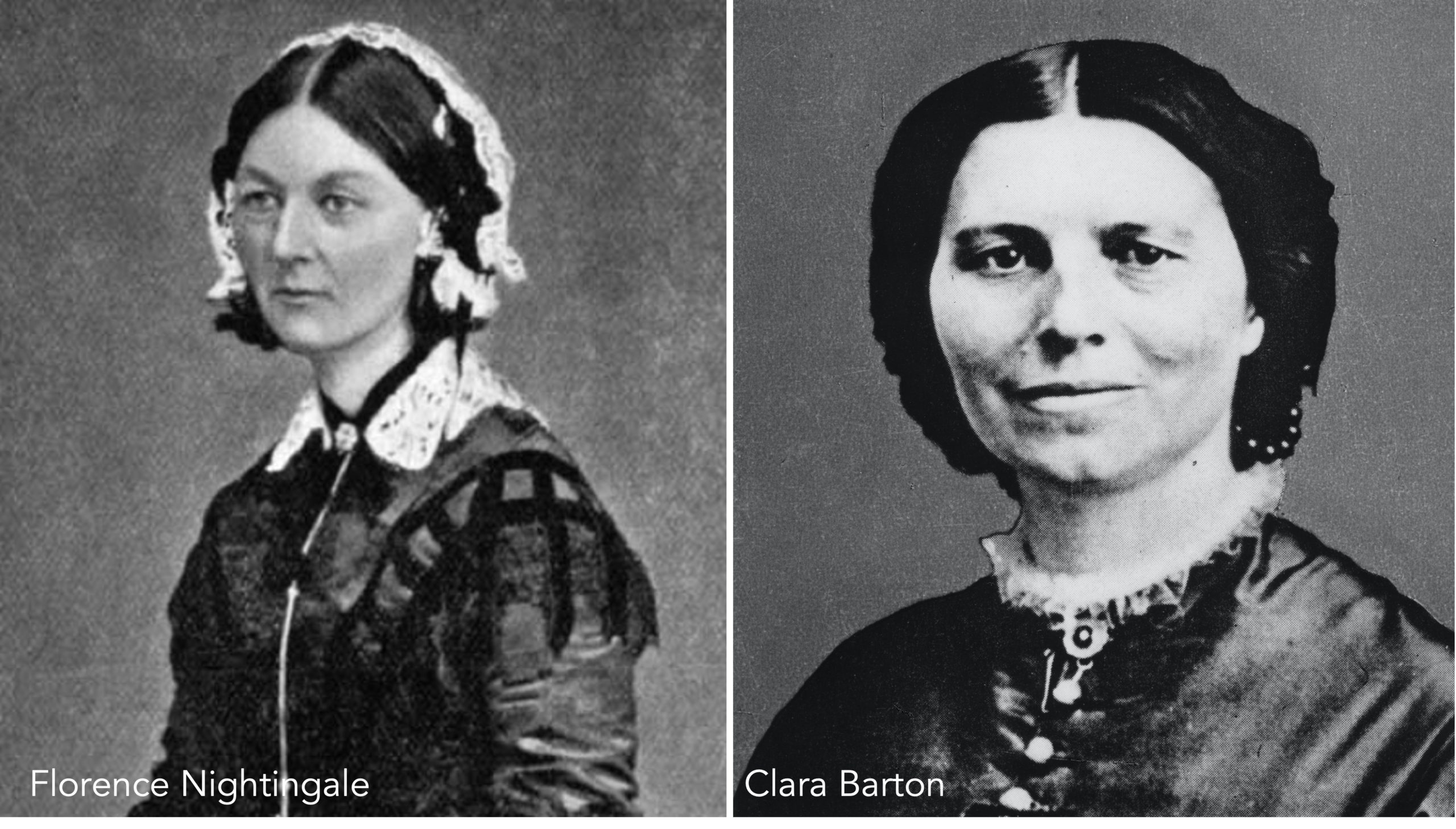

Relief to the Wounded

Wartime medical aid to the wounded was obviously not new. Dunant’s genius was to formalize it, but many of his contemporaries practiced it to a much greater extent than Dunant himself. In particular, women played a leading role in pioneering wartime nursing. Britain’s Florence Nightingale was greatly admired by Dunant. Clara Barton had extensive experience of frontline nursing in the US Civil War and went on to found the American Red Cross.

Pioneers of wartime nursing

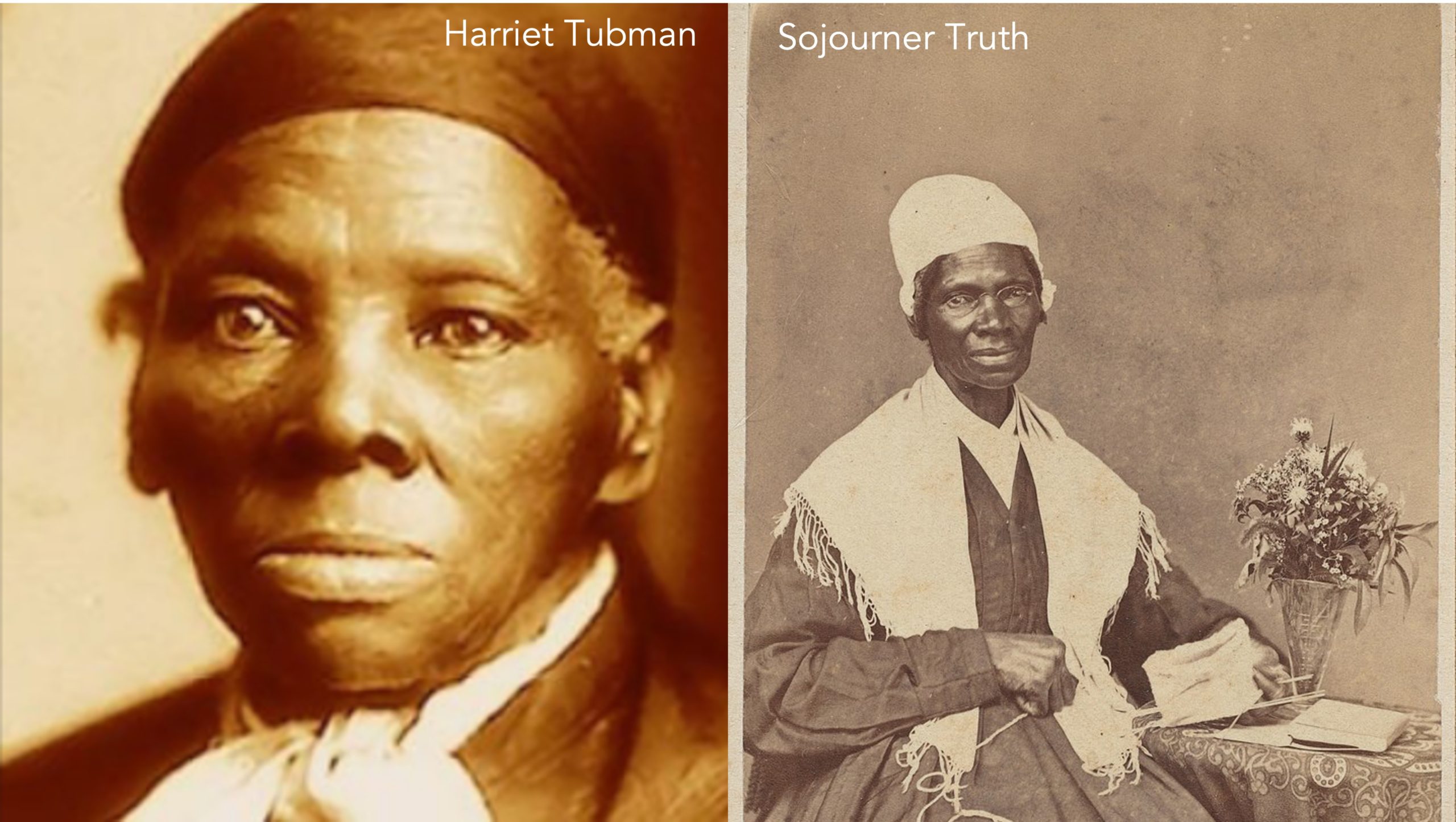

Three other women were pioneers of wartime nursing too but were largely overlooked because they were black. Mary Seacole worked near Nightingale in the Crimean War in the mid-1850s. Two great US abolitionists, Harriet Tubman and Sojourner Truth, worked as nurses in the American Civil War in the decade after Solferino.

But it was really World War I that saw an exponential expansion of wartime aid.

Between 1914 and 1918, the ICRC and many National Red Cross Societies expanded their operations dramatically in medical care for the wounded.

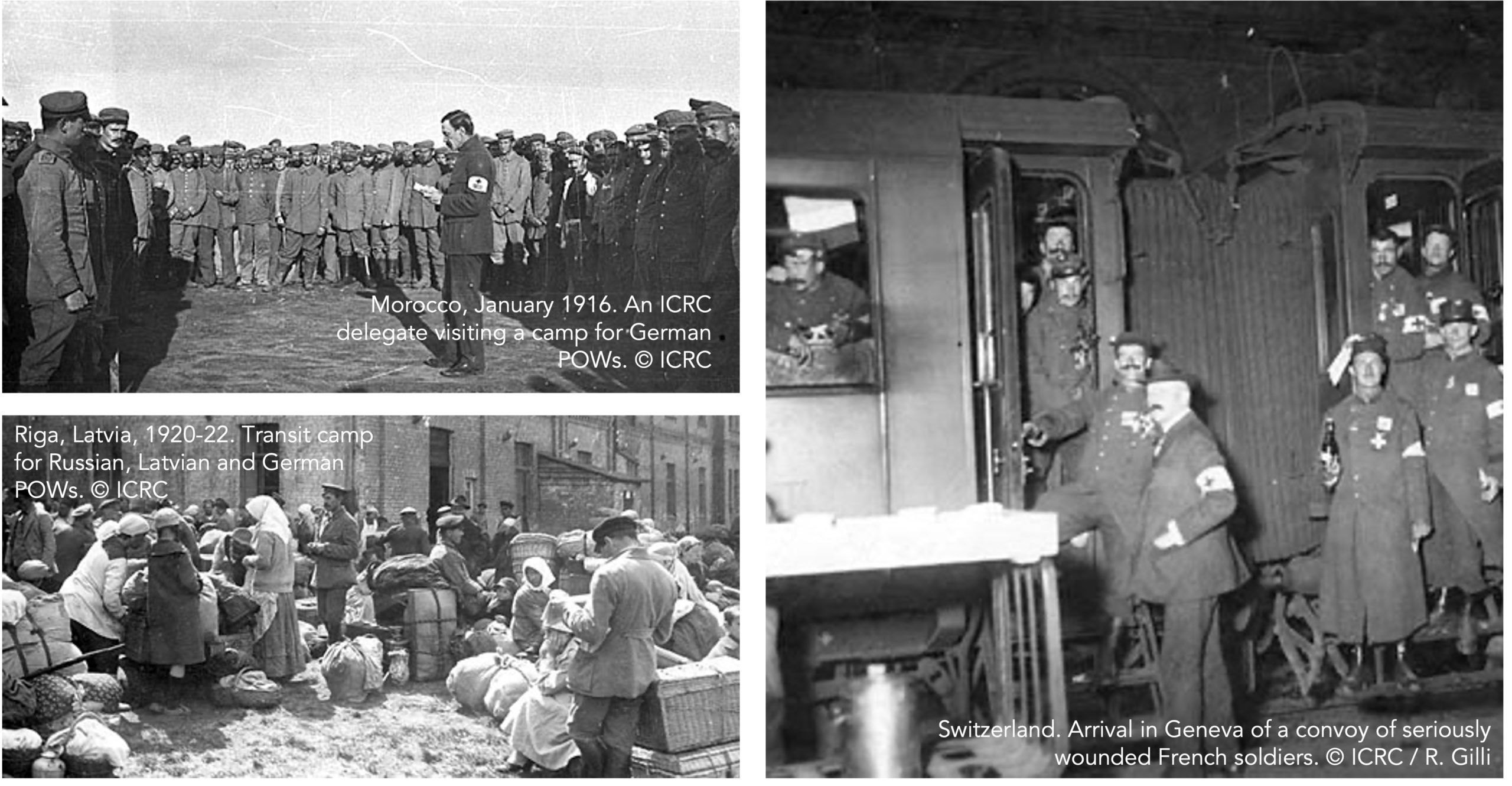

Aid to Prisoners of War

A particularly important innovation in World War I was work in support of prisoners of war led by the ICRC and the wider Red Cross and Red Crescent. Together, they pioneered a major new field of humanitarian practice for Dunant’s successors. After the war, it was enshrined by States in a new Geneva Convention to protect prisoners of war in 1929.

Aid to civilians

Popular stereotypes of World War I present its suffering as experienced by soldiers in the trenches. In fact, an estimated 10 million civilians died from destitution, disease and atrocity, probably more than combatant deaths.

The Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement joined in a much wider effort to aid the civilian populations of Europe and the many war-torn Arab, Asian and African countries during and after World War I.

But the real momentum for civilian relief came from an exceptional American.

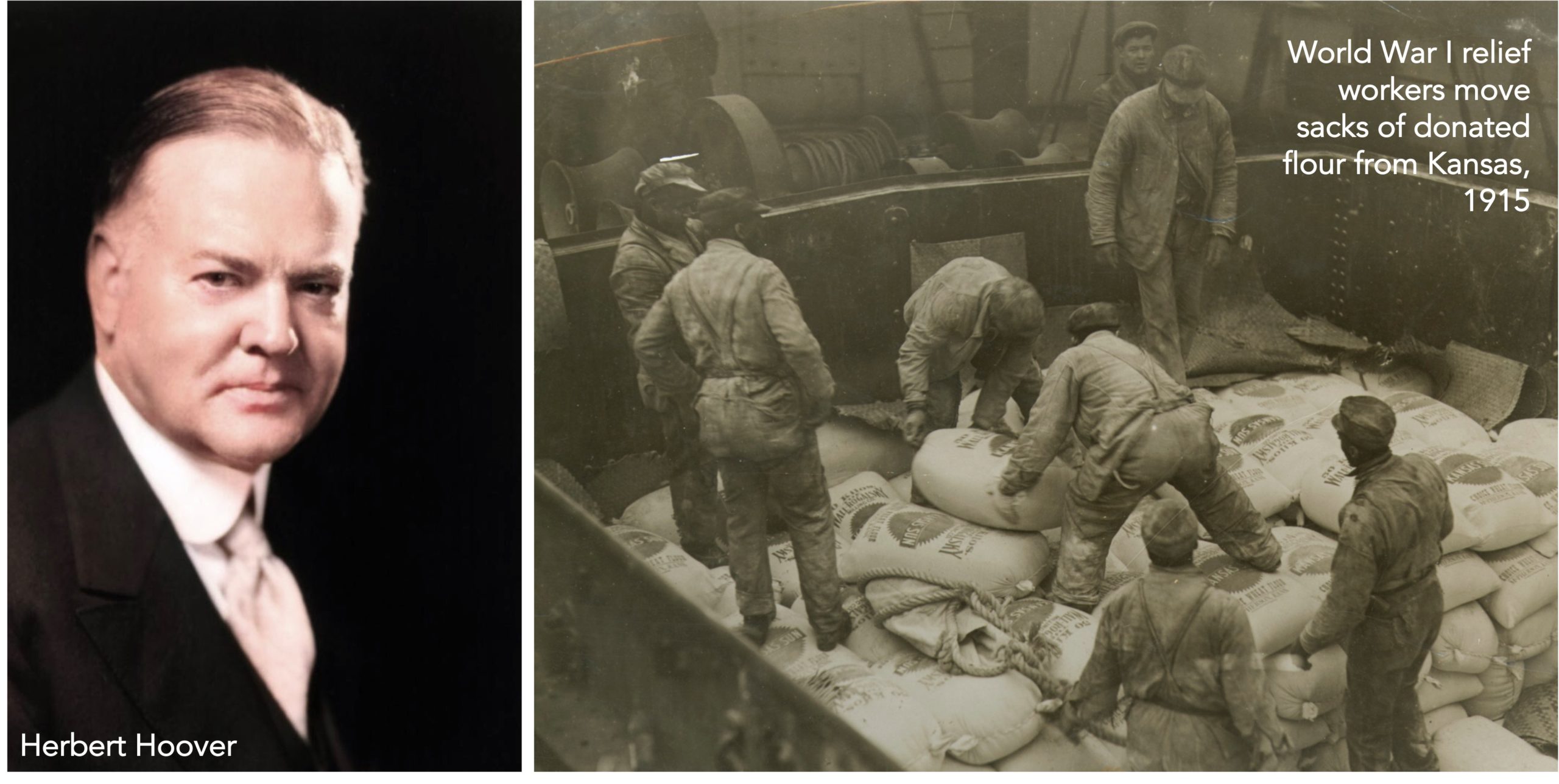

Herbert Hoover was raised in poverty and became a mining magnate in China and London before turning humanitarian at the onset of World War I and eventually becoming President of the USA. He was one of many dedicated Quakers working in wartime relief.

Hoover is probably the greatest Western humanitarian of all time and certainly had the largest operational impact of any single individual.

In a matter of months, he pioneered humanitarian food operations of industrial scale for hundreds of millions of people to match the industrial warfare and Spanish flu that was killing and impoverishing them. Hoover’s massive American food relief operations to occupied Belgium and France were followed by European-wide post-war relief and the largest single relief operation in the Russian Civil War.

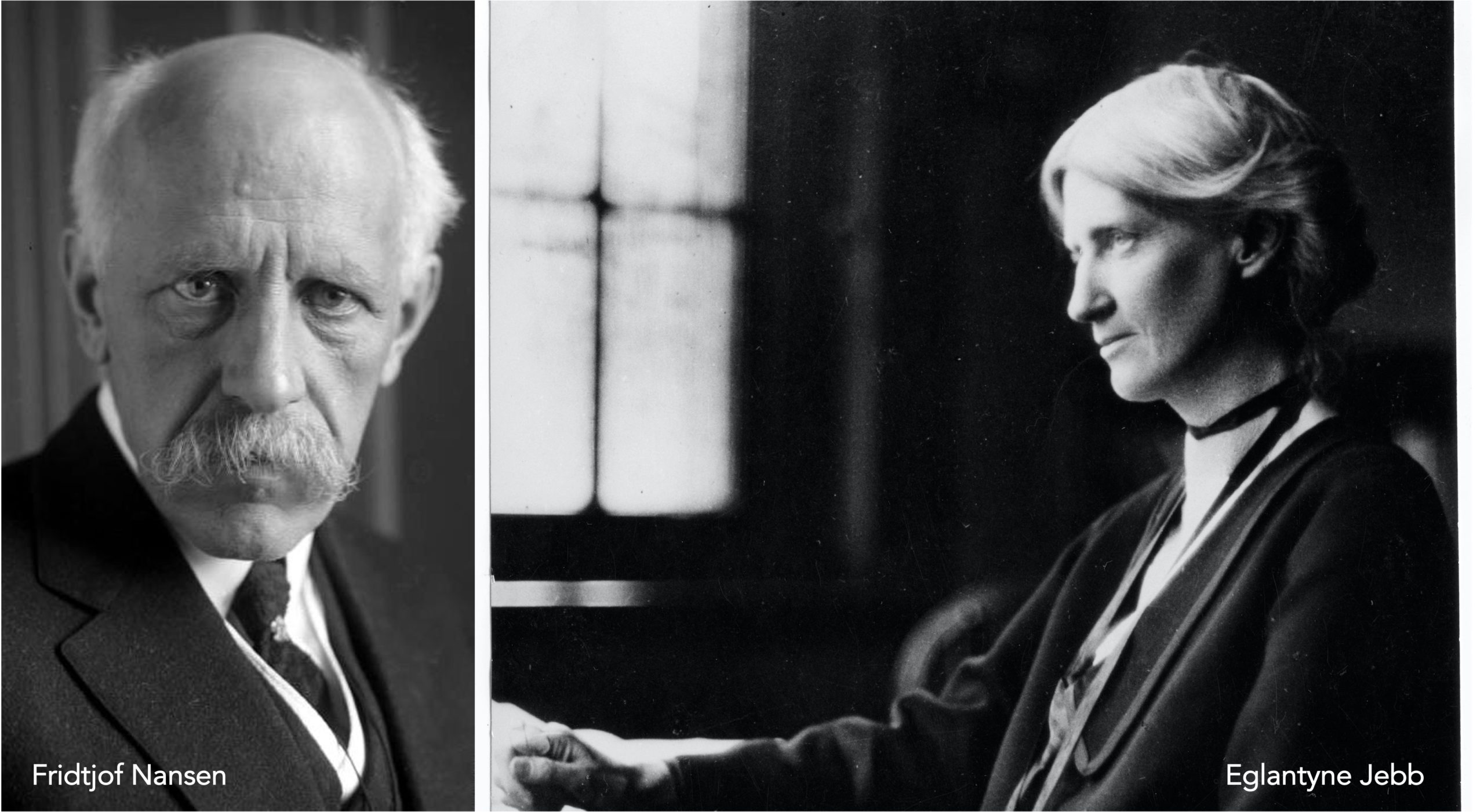

At the same time, the great Norwegian, Fridtjof Nansen, was pioneering the protection of refugees and huge prisoner repatriation programmes. A group of well-connected English radicals set up Save the Children which was led by Eglantyne Jebb. Her efforts put children on the international humanitarian agenda.

The League of Nations which followed World War I began to formalize all these humanitarian concerns into various international agencies which later developed into UN Specialized Agencies like UNHCR, UNICEF, WHO and the World Food Programme.

Every conflict since World War I has produced new international non-governmental humanitarian organizations out of Europe and North America.

Plan International was founded in the Spanish Civil War. The International Rescue Committee (IRC), Oxfam and CARE emerged in World War II. Shortly afterwards, churches began organizing global relief and development organizations like Caritas, the global Catholic network. World Vision was founded in the Korean War. Concern Worldwide and Medicins Sans Frontieres took off in the Biafran War; Mercy Corps and Handicap International (HI) in the Cambodian genocide, and Islamic Relief in the Ethiopian famine of 1984.

These wars were the launch period for the NGO moment in humanitarian aid which saw a particular surge from the 1960s onwards.

From the 1970s onwards, Western humanitarian aid has also been profoundly influenced by major discoveries by South Asian, African and Latin American activists.

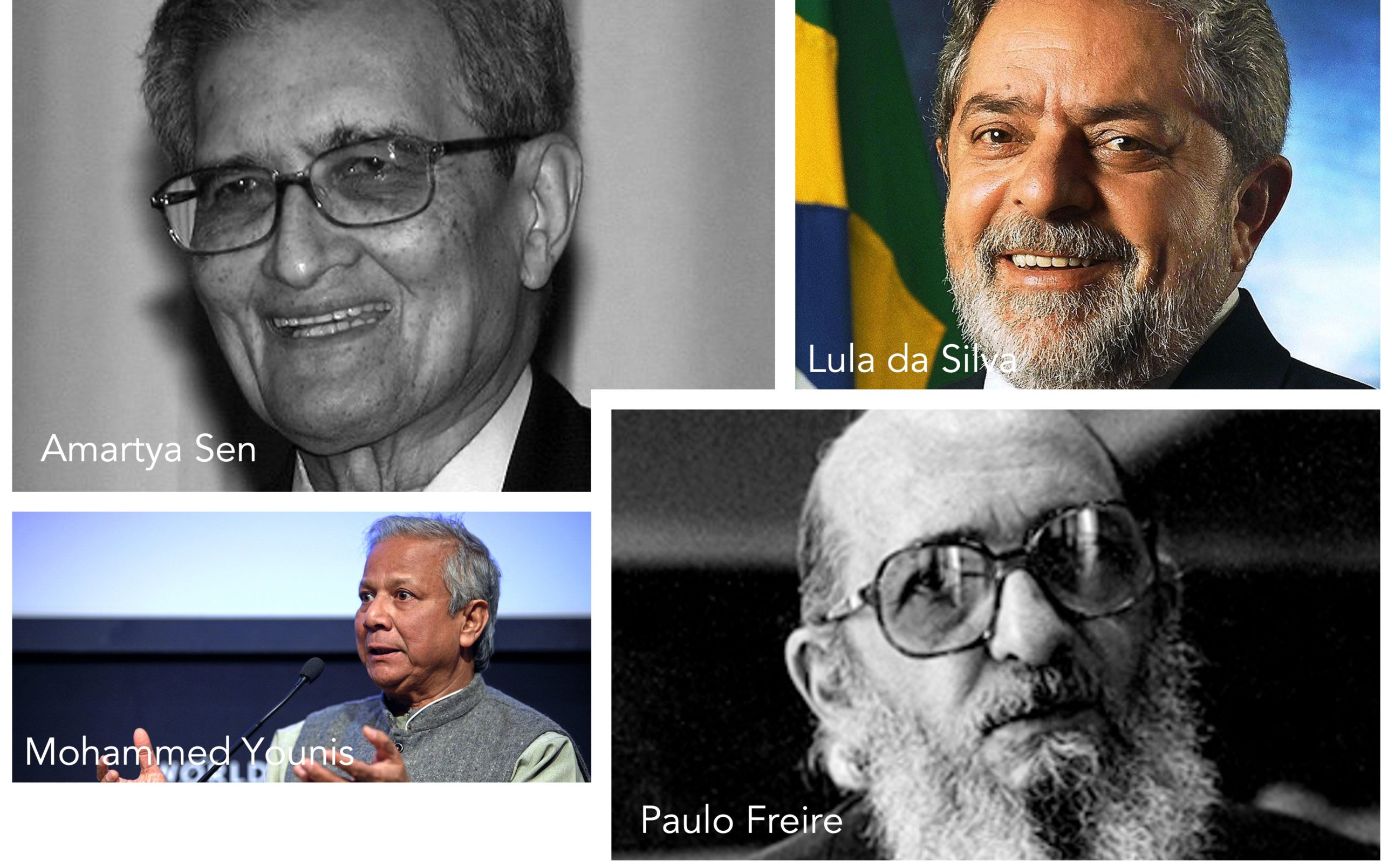

Amartya Sen changed the way humanitarian agencies understood famine and hunger. Mohammed Younis launched the movement for pro-poor cash transfers that inspired the recent move to cash-based aid. Brazilian Paulo Freire, African anti-apartheid activists and Latin American “liberation theologians” in the 1970s and 1980s introduced influential methods of community empowerment and resistance-based humanitarianism. Former Brazilian President, Lula da Silva’s nationwide Bolsa Familia programme in the early 2000s encouraged humanitarian economists into social protection programming.

Humanitarian improvements

The numerous wars, wartime famines, epidemics and genocides of the 20th century gave humanitarians a succession of tragic opportunities to expand and improve their profession. This humanitarian history is now a growing field of academic study.

New advances in humanitarian medicine, emergency nutrition, food aid, shelter, water and sanitation were accompanied by developments in humanitarian social work in family tracing and psycho-social programmes.

Humanitarian economics developed fast in a dual concern for “lives and livelihoods” that saw humanitarians developing food for work and cash for work schemes, and slowly adopting individual cash transfers as a major part of emergency aid.

From the 1970s onwards, humanitarians also worked hard on early warning and disaster prevention systems for famine, hunger and natural disasters, especially across the Sahel where famine repeatedly threatened to recur. Much of this work was pioneered by the US-led Famine Early Warning Systems network (FEWS) and by Save the Children, the Institute of Development Studies and FAO. It was greatly enhanced by the arrival of satellite and computer technology.

This investment in the organizations, science, practice and international norms of humanitarian aid led to hundreds of millions of human lives being saved and supported throughout the 20th century, even when so many other lives were lost to war, genocide, wartime famine and disease.

Much of this progress was profoundly entrepreneurial, born out of pioneering individuals in highly creative and risk-taking organizations. The results were impressive and international humanitarian aid stands as a major ethical, legal and operational achievement in modern international relations between peoples and states.

Humanitarian Laws and Principles

Throughout the 20th century period, the laws of war developed too in a long series of international treaties: Hague Conventions, Geneva Conventions and UN Conventions. These protected particular groups in war, regulated the conduct of hostilities, and agreed on disarmament measures and arms control.

From the 1960s onwards, the laws of war became more commonly known as “international humanitarian law” (IHL). These international laws started with Dunant’s original Geneva Convention for the wounded in 1864 and have most recently culminated in the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons in 2021.

Alongside international law, humanitarians also developed ethical principles of action. In 1965, the Red Cross and Red Crescent Movement agreed its seven humanitarian principles.

The first three of these – humanity, impartiality and neutrality – were formally taken up by the United Nations in UN General Assembly Resolution 46/182, adopted in December 1991.

In 1994, many humanitarian agencies adopted the 10 principles of the International Code of Conduct, which include important operational commitments on how to work ethically with affected people and societies. In 1997, many international NGOs agreed and adopted the Humanitarian Charter and SPHERE standards, which give detailed technical guidance on what constitutes good practice in humanitarian health, shelter, nutrition, water and sanitation, gender and protection.

These various laws, principles and standards established an ethical and operational orthodoxy for the practice of international humanitarian aid.

Humanitarian expansion in the 2000s

At the beginning of the 21st century, many of non-governmental, Red Cross/Crescent and UN organizations pioneering in the humanitarian arena had become large transnational bureaucracies.

Together, these organizations formed what came to be called the “international humanitarian system” and they were funded from the tax base of Western governments, with additional private donations from Western publics, private foundations and high street trading in fair trade and second-hand goods.

Between 2000 and 2021, the annual budget for this humanitarian system rose from $5.9bn to $30.9bn and the sector saw exponential growth – a humanitarian boom. Western governments expanded aid to people affected by armed conflicts all around the world, and war aid eclipsed aid for climate-related and geological disasters.

The scale and operational reach of the system became consistently monitored by the United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs – OCHA and by the more independent Global Humanitarian Assistance’s annual report.

Operational oversight of the humanitarian system became coordinated and controlled by the Inter-Agency Standing Committee – IASC – which is chaired by the UN’s Emergency Relief Coordinator and includes all major UN, Red Cross and NGO organizations. The IASC sets policy and operational priorities for the system.

The humanitarian shadow

Like every great human project, humanitarian aid casts shadow as well as light. The humanitarian shadow has been a colonial one as largely white Western agencies frequently exuded implicit racial superiority in the way they took control of crisis in other countries and in other people’s lives.

This attitude was evident in the gaze of many dominant images of wartime need and humanitarian action throughout the second half of the twentieth century. Photographs and film footage consistently portrayed a narrative of suffering black and brown bodies being saved by white experts.

This racist shadow with its superior mindset and tropes became increasingly recognized and challenged as “disaster pornography” from the 1980s onwards and was specifically addressed in article 10 of the 1994 Code of Conduct.

Humanitarian elaboration in the 2000s

Bigger bureaucracies, excess staff and continual budget increases naturally led to an extensive elaboration of humanitarian aid in the first two decades of the 21st century.

Humanitarian ambition increased dramatically. The big players in the humanitarian sector began to conceive of their system as being able to provide a worldwide safety net for all people affected by war. In human rights law and international humanitarian law, they also found reason to offer help that stretched far beyond Dunant’s humanitarian vision of medical care, food, water and family contact.

This new humanitarian ambition expanded in five main areas:

Elaborating humanity

Western liberal humanitarians have been inspired by human rights and modern social theory to elaborate their core value of humanity.

No longer do humanitarians see humanity as a singular identity of simply being human. A deeper appreciation of differences in gender, race, colour, culture, age, class and ability have created a more complicated sense of humanity as diverse and different in each person.

This commitment to the principle of diverse humanity makes aid programming more intricate and more dependent on complicated social analysis and assessment as a prelude and condition to the distribution of aid.

Widening needs

Just as humanitarian agencies have more staff and money to analyse, assess and allocate, they also have more time to discover and prioritize more human needs.

The expansion of five new fields of humanitarian action particularly stand out. Protection, mental health, education, climate adaptation and accountability have all become major new specialisms in the humanitarian sector in the last twenty years. Each area demands new specialists, detailed standards and large budgets.

Digital space and digital money

Digital technology is transforming humanitarian aid assessment and distribution.

This is perhaps best seen in the gradual consolidation of global humanitarian data, which is increasingly being pooled and shared by the UN’s new Humanitarian Data Exchange in The Hague. Also evident is the sector’s big shift towards digital cash transfers as a major means of helping people. In 2004 only 1% of humanitarian aid was given as cash. In 2019, the CALP Network reported that cash transfers have risen to 18% and continues to rise.

Increasingly, humanitarians are also operating as virtual agencies in virtual spaces to connect with people’s virtual lives, alongside their physical lives. In February 2022, the ICRC launched its first Delegation in Cyber Space. A great part of humanitarian time is now spent monitoring and engaging with warfare in cyberspace, protecting humanitarian data, and countering strategies of misinformation, disinformation and hate speech in virtual space.

Long aid and the extension of humanitarian time

Humanitarians have unanimously adopted a long-term time horizon for their work in a system-wide desire that their aid should have a sustainable impact of some kind in people’s lives. This means that humanitarian programmes are increasingly focused on long aid rather than short term relief.

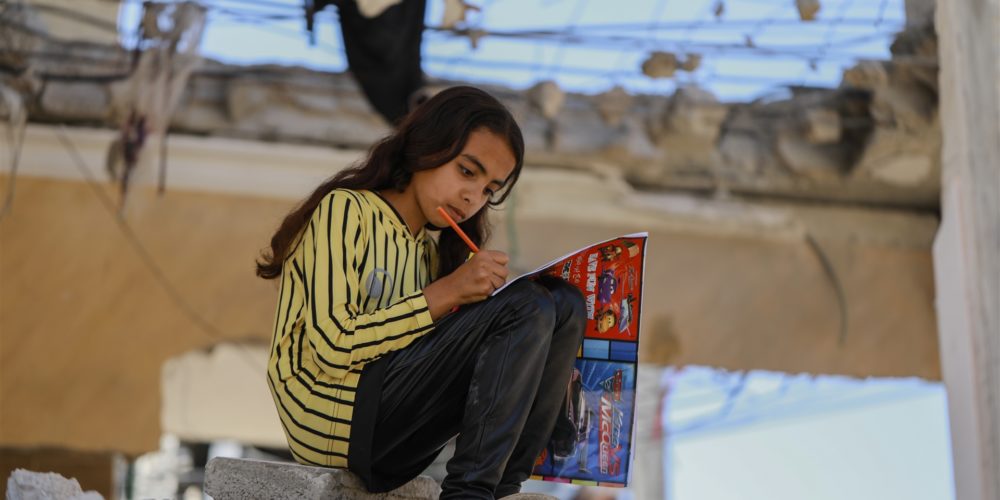

Most humanitarians today are not working in the immediate violence of war and real-time destruction but rather with large groups of people enduring the consequences of war for many years in unplanned urban settlements of displaced people or badly damaged and deprived rural areas. Many agencies are in their second or third decade of work with communities in Afghanistan, Myanmar, Iraq, Syria, South Sudan and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

In the early twenty first century, most humanitarian organizations are operating like UNRWA in Gaza, not Oxfam and MSF in Cambodia.

Globalizing welfare

The widening of humanitarian activities and the extension of their time horizon means that many humanitarian agencies are effectively and deliberately engaged in long-term welfare provision to hundreds of millions of people worldwide.

The development of social protection systems is now becoming a priority for many organizations as they team up with existing government social protection systems, or operate their own parallel systems. This approach has surged during the COVID crisis and been closely monitored by Ugo Gentilini at the World Bank.

Working with governments, humanitarians are specializing in shock responsive social protection, in which their cash programmes expand and top-up existing government social protection during spikes in conflict and climate-related disaster.

Looking ahead, social protection is likely to be the big system people will need for the intense periods of climate crisis coming towards them in the next ten years.

Changing Humanitarians

In 2022, the international humanitarian system is shaped by its four big twenty first century trends:

The boom in Western humanitarian budgets in the century so far

The dominance of international superagencies

The increased ambition of these agencies

The elaboration of humanitarian ideology and activity by ever larger staffs.

The resulting humanitarian system has certain characteristics that need changing.

A Western Club

What is called the “international humanitarian system” today is certainly international, as it has been developed by the collective action of many states. But it is neither a global system nor a globally representative one. It is fundamentally a Western system designed and largely financed by Western liberal states who are all members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), and whose policies are coordinated and evaluated by the Development Assistance Committee (DAC) of the OECD.

Global powers like China, Russia and India stand back from this Western system and treat it with suspicion as pervasive of liberal values and a threat to national sovereignty because of its tendency to “interfere” in the internal affairs of crisis states. Nor does the Inter-Agency Standing Committee – IASC or its sister initiative, the Grand Bargain, make any real space to include crisis affected countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America. Instead, it makes humanitarian policy for these countries without their involvement.

A colonial approach

The humanitarian superagencies dominate financing and operations too. Their huge footprint employs thousands of people with humanitarian power held firmly in a highly paid “expatocracy” that lives largely detached from wider society in privileged colonies of team houses, elite restaurants, big cars and bright flags.

The main business model of the big agencies continues to be a top-down internationally driven approach from their global headquarters, and those of their government donors, in Western capitals, Geneva and New York.

The struggle for a more devolved system

The expanded and largely Western system of international humanitarian aid has saved and supported hundreds of millions of lives in the 21st century. However, there is an increasing concern by many in the sector that it is now too international, exceedingly centralized and overly dominated by a few big agencies.

As a result, there are moves to bring about much greater “localization” of the sector, which brings humanitarian power and resources much closer to the ground in nationally and locally-led humanitarian organizations.

This shift is seen as an issue of political justice and self-determination, and is also deemed essential if humanitarians are to stand any chance of coping with the much bigger demands of the climate crisis and big war. Bigger and bigger international agencies will be increasingly bad value for money as they become operationally rigid, overstretched and intensely bureaucratic.

Instead, international humanitarians need to lean in much more to Dunant’s original vision of a network of national humanitarian organizations created by committed citizens that are supported by governments and complemented by international agencies.

Greater Humanitarian Cooperation

This means international organizations should step back in large part from their current operational model of humanitarian action, which sees them serving large caseloads of individuals. Instead, they should adopt a model of humanitarian cooperation which sees them actively investing in the locally-led humanitarian action of national and community partners. In business terms, this is a switch from a business-to-customer model (B2C) to a business-to-business model (B2B) – as internationals become creative investors in a portfolio of organizations rather than direct providers to long lists of individual recipients.

At a global level, today’s new multipolar world requires humanitarian cooperation too. Geopolitics dictates that the Western-funded humanitarian system will never be the single global system. Its sphere of influence and access will always be profoundly limited in large parts of the world where people experience war and climate disasters in spheres of influence controlled by China, Russia, India and anti-Western Islamism.

Realistically, international humanitarian agencies should accept that the global humanitarian system must be a “system of systems” and not the globalization of the Western system. Humanitarian multilateralism in the 21st century will be about achieving cooperation and coordination between Chinese, Indian, African, Western, Russian and Indian humanitarian systems in a process more like the COP of climate multilateralism than the IASC of today’s parochial Western system.

Simpler aid

Finally, simpler aid must be a priority in all humanitarian systems. The last 160 years have produced enormous progress in humanitarian aid. But the increasing complexity of humanitarian aid is now a significant and expensive characteristic of the system.

The sheer volume of guidelines and standards required in the assessment, delivery, monitoring, evaluation and accountability requirements cries out for greater simplicity. The sector also needs a much clearer sense of strategic purpose instead of the many different social, economic and human rights objectives it is currently pursuing in its utopian “do everything” approach to crisis

Dunant’s two challenges still matter

In 1862, Dunant posed two main challenges to governments and concerned citizens: to agree clear limits to human violence, and to better organize our compassion and aid.

He would stand amazed today at the huge progress that has been made to rise to his challenge in the last 160 years: new laws; new organizations; hundreds of billions of dollars, and many millions of humanitarian volunteers and aid agency employees have played their part to transform the humanitarian landscape in war.

But Dunant’s challenge is a perpetual one. New forms of war, new technologies, new geopolitics, new diseases and new climate-related crisis mean that this work is never done.

The need for humanitarian work and humanitarian improvements continues.

Explore the project

Dunant’s original humanitarian vision

Warfare today and tomorrow

Civilian experience of war